Phases of Athlete Development in an Age Group Program

The following is an outline description of the four phases of development and the basic premises that currently guide our thinking at each of these levels. The DCY SWIM program mirrors this age group rationale.

Published

June 1, 2000

Author

By ASCA

By Pat Hogan, Mecklenburg Aquatic Club, North Carolina

The Mecklenburg Aquatic Club program has been structured on the premise that there are four basic phases of athlete development in age group swimming. At each level of the program, we continually try to evaluate and adapt to the multitude of factors, both scientific and sociological, that impact the growth and development of young athletes. Experience has taught us that the perfect age group program is a moving target that changes as the population we serve changes and as we learn more and more about the development of young people.

The following is an outline description of the four phases of development and the basic premises that currently guide our thinking at each of these levels. The final page of this packet is a chart, which provides an overview of the entire MAC program.

Phase I: Basic Skill Development – Ages 11 & Under

This phase is the introductory level of competitive swimming. In order to begin in the novice levels of our program, swimmers must be able to swim a minimum of 25 yards freestyle and backstroke.

1.The focus is almost entirely on teaching fundamentals and developing basic motor learning skills, balance and coordination in the water.

2.We believe young athletes should begin swimming on a regular basis no later than age 9 or 10, ideally at age 7 or 8. How far they swim is not as important as the fact that they are in the water on a regular basis developing their feel for the water. We believe it is important that novice competitors swim at least 2 times per week for a minimum of 7-8 months per year.

3.It is vitally important to make swimming fun and enjoyable. We believe the most significant responsibility for novice coaches is teaching young people to love the water and to love the sport.

4.It is critical for novice coaches to emphasize correct fundamentals and to have the willingness to sacrifice speed for efficiency. This concept can sometimes work against a swimmer’s short-term success at this age. At this level, we believe there is great merit in competition based on skill development.

5.The majority of yardage in the early years needs to be low intensity and technique-oriented. This is not necessarily as exciting or fun for swimmer or coach, as is swimming fast.

6.We believe that it is essential to teach, develop and promote all four strokes and all events. Age groupers should not be permitted to specialize in practice or in meets.

7.We place a very heavy emphasis on kicking. Coaches are required to make kicking a high percentage of the conditioning work done at the novice levels. Kickboards are the only training aids used at this level.

8.Swimmers are readily encouraged to participate in other activities and sports. We believe physical activity and the experience of other sports increases the number of learned movement patterns and general athletic development of the child. Sports such as gymnastics and soccer have excellent carryover value. The better the athlete, the better the swimmer.

9.At every level, but particularly the novice level, we take a long-term approach to swimmer development. Once swimmers begin in our program, we want to give them the preparation and tools they will need to make swimming a lifetime activity.

Phase II: Basic Training Development – Ages 11 to 14

At the age of 11-14, swimmers move into the second level of our age group program. Swimmers who move into these practice levels are able to swim all four strokes and maintain good technique on low intensity interval work. This phase is a transitional level where the emphasis begins to change from primarily teaching to a relatively equal balance of technique work and physiological development.

1.The focus is still centered on teaching fundamentals and developing a strong foundation in all strokes.

2.The number of practices per week offered at each team level increases to 5-6 and swimmers are encouraged to attend as many practices as possible but no fewer than 4 per week.

3.Low intensity aerobic conditioning is emphasized and athletes begin to do more mileage on a weekly basis. It is important that the fundamental skills developed in Phase I not be compromised as swimmers begin to swim farther in practice.

4.At this level, the training program focuses on preparation for the 200 IM and 200/500 freestyle events. Even if swimmers show promise in specific events, we do very little specialty work. We have developed a program that we call “IM Tuff” to promote interest and participation in the IM and, eventually, the distance freestyle events.

5.A high priority continues to be placed on kicking all four strokes. Beginning at this level, coaches are encouraged to do 40-50% of their kick training without boards.

6.Beginning with this phase a high priority is also placed on maximizing the number of training weeks per year. Peak performance efforts are put off until the latest point possible in each season. Likewise, the importance of swimming through the year is emphasized. This training philosophy carries through to the higher levels of the program.

7.Swimmers are still encouraged to participate in other activities and sports. However, we are hopeful that participation in other activities allows them to meet the minimum attendance expectations for swimming. In a perfect program, the swim team would provide opportunities for crossover training and exposure to other sports.

8.Stretching and limited calisthenics are incorporated into the overall program during this phase.

9.Although the overall level of training expected of swimmers increases during this phase of the program, coaches are charged with being creative and making the experience fun and enjoyable. Great age group coaches have the special ability to make hard work be fun.

Phase III: Progressive Training – Ages 13 to 18

Most team members move into the senior levels of our program at age 13. The quantity and intensity of the training program increases. For the first time, the program structure calls for more time to be devoted to physiological conditioning than to teaching fundamentals.

1.n this phase, the mileage completed each week begins to be an important consideration. We want to take advantage of the pre-pubescent window of opportunity to more fully develop aerobic capacity.

2.Although low intensity aerobic conditioning is still the highest priority, we have athletes begin to do more anaerobic threshold work. As swimmers swim faster in practice a greater percentage of the time, it is critical that technique is not compromised.

3.At this level, the training program focuses on preparation for the 400 IM and middle distance freestyle events. Even if swimmers show promise in specific events, we do very little specialty work. The IM Tuff program is a prominent focus within these practice groups.

4.We believe that to be as successful in long course swimming as one is in short course swimming requires approximately 10-15% better conditioning. The training program in the practice levels of Phases III and IV is designed to emphasize and promote long course swimming throughout the year.

5.Swimmers are encouraged to attend as many practices each week as possible. AM practices during the school year are introduced at the top level of this phase. All three groups are provided the opportunity to do two-a-day practices during the summer months. Swimmers at these senior levels are encouraged to begin to make a choice between swimming and other activities.

6.Beginning in this phase, careful attention is given to maintaining aerobic fitness levels from one season to the next. Breaks between seasons are limited to avoid significant deterioration of aerobic fitness.

7.Dryland training is introduced at these levels with the emphasis primarily being on the development of core body conditioning and teaching swimmers how to lift weights.

Phase IV: Advanced Training – Ages 14 & Over

Swimmers with the appropriate dedication, desire, experience, and talent move to the advanced training level of our program at 14-15 years of age. The training program in Phase IV is very demanding with a heavy emphasis on distance-based physiological training.

1.Success over the long-term remains a high priority. Although we could train high school age swimmers in such a way that they could swim faster in the shorter events during their teenage years, we believe it is our responsibility to provide an aerobic-based training foundation that will allow them to achieve ultimate success in their college years.

2.Work within various energy systems becomes an important component of the overall training program. Emphasis is still heavily aerobic, but specificity of training for stroke and distance becomes part of the regimen.

3.While mileage completed is an important consideration, attention to detail and improvement in stroke technique is very highly valued. Coaches continually stress efficiency and technical precision as key components to success at the elite levels.

4.Swimmers are still encouraged to train and compete in a wide variety of events. We believe there are many instances in this country where 14-17 year-old swimmers begin to specialize too early in their careers.

5.The commitment level required at these levels of the program is very high with swimmers expected to attend 8-9 practices per week during the school year and 9-10 practices per week during the summer.

6.Strength training with free weights and machines is a standard part of the training program.

https://swimmingcoach.org/phases-of-athlete-development-in-an-age-group-program/

The Importance of "Self Confidence" in Achieving Your Swimming Goals

The following article by Wayne Goldsmith has been extracted from the website of the American Swimming Coaches Association:

Have you said (or thought) any of the following in the past few months??? "I can't do it," "They are much faster than me. I'll come last," "I'm hopeless," "I've never been able to do that, so I know I can't do it now," "It's just too hard. It's impossible."

You are not alone. Many swimmers have these thoughts and say these words from time to time. Most swimmers (and people generally) have times when they get a little negative and lack faith in their abilities. When swimmers say "I can't" or "it's too hard," what are they really saying?

Swimmer says: "I can't do it." Swimmer means: "I am not prepared to try because if people might think less of me."

Swimmer says: "They are faster than me. I'll come last." Swimmer means: "If I can't win there's no point trying."

Swimmer says: "I'm hopeless." Swimmer means: "I have no faith in myself or my ability to succeed. I have no confidence."

Swimmer says: "I've never been able to do that, so I know I can't do it now." Swimmer means: "I've never really prepared for this or learnt how to do it correctly so the chances of me doing it now are not very good" or "I tried once and failed, so I am not going to try again."

Swimmer says: "It's just too hard. It's impossible." Swimmer means: "I'm not prepared to try."

Confidence is believing in yourself to do what has to be done. To do what needs to be done, with faith in your ability to achieve it. To meet new challenges with an expectation that anything is possible. To accept failure as an opportunity to learn from the experience and try again. And try again. And try again if necessary.

Confidence is trying to achieve and if you fail knowing that it was the nature of the task or the circumstances or just plain bad luck, not your lack of character that is to blame. Confidence is learning from that failure and trying again with more energy, more commitment and greater determination than before.

What do some of Australia's most successful people say about CONFIDENCE??

"Confidence comes from accepting a challenge and achieving it using the best of your ability. Confidence builds through training to meet your challenge." - Phil Rogers (Commonwealth Games and Olympic Medallist)

"Confidence is about believing in yourself and your ability to do something - not necessarily believing in your ability to do it perfectly or better than other people, but believing that you have as good a chance as anyone to achieve something. Confidence is having the courage to get up and try and face whatever the outcome is - good, bad or something in between." - Chloe Flutter (Australian Representative Swimmer, now Rhodes scholar)

"In my experience, confidence is best achieved through controlled independence. If a young athlete is constantly challenged to be independent (within reasonable bounds), they will learn to rely on themselves and know how to thrive without the assistance of others in moments of greatest need. The ability to follow good decision making processes is a crucial part of this. For young athletes, teach them to take personal responsibility ( control the controllable and develop a chameleon-like ability to deal with the rest). Confidence is the ability to believe you can do something and the courage to do it - if others have made the hard decisions for you and you have never had to live with the results of your own actions, you can never be expected to know full confidence and the power of the self." - Marty Roberts (Dual Olympian, Commonwealth Games Gold medallist, University Graduate, father of two)

"Attitudes such as belief, optimism, high aspirations, and anticipation of the best possible result—all these positive states of mind add up to confidence, the keystone for success. But of course it pays for all of these to be built on the firm rock of a sound preparation." - Forbes Carlile (Legendary Coach, successful business man, author, leading anti-drugs in sport campaigner)

Confidence it seems, is a skill -- a skill that can be learnt. You learnt to swim. You learnt to tumble turn. You learnt how to do butterfly. You can learn to be confident.

Leading Melbourne based Sports Psychologist, Dr Mark Andersen agrees: "Many people believe that confidence is something that comes from the inside, but we probably develop confidence from the models we have around us, that confidence really comes from the outside. If we have coaches, parents, teachers and instructors that model confidence in our abilities and let us know that they think we can do good things, slowly their confidence in us becomes internalised."

A Few Tips to Develop Confidence:

• Accept who you are and learn to like and respect yourself.

• Nothing helps build confidence like learning the 3 P's:

• Practice to the best of your ability.

• Develop a Positive Attitude to trying new tasks.

• Persevere, Persevere, Persevere.

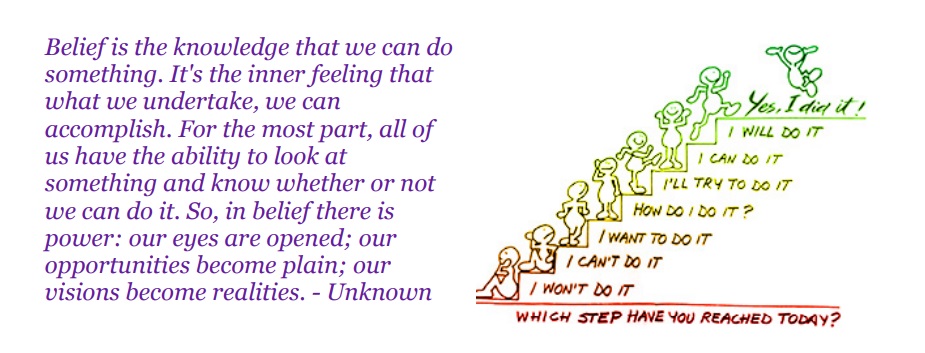

Ladder of Achievement

100% I Did

90% I Will

80% I Can

70% I Think I Can

60% I Might

50% I Think I Might

40 % What is It?

30% I Wish I Could

20% I Don't Know How

10% I Can't

0% I Won't

This is called the Ladder of Achievement. It shows how your attitude towards a goal or task can impact your ability to achieve it. The ladder of achievement suggests that an attitude of "I can't" has almost no chance of success whilst "I won't" is no chance at all.

Change "I can't" and "I won't" to I CAN - I WILL - I DID! Understand what motivates you to do well then you can harness your energy in the right directions.

Failure is a race or a meet or a task -it is not a person. Failure is not the person: it's not you- it's the performance. Learn to separate who you are from what you do.

Learn to talk to yourself positively. When the negative thoughts come, learn to replace them with positive ones. I can't = I can, I won't = I will, I will try = I did. Remember the old saying, "If you think you can or think you can't, you're probably right."

"The greatest achievement is not in never failing but in getting up every time you fall." Keep trying and it will happen. What you believe, you can, with effort and persistence, achieve. Dream a dream, believe in that dream, work towards achieving it and live the dream.

Anything worth having is worth working to achieve. Talent is important, but there are many talented swimmers who don't make it to the top. TOUGH, TENACIOUS TRAINING makes up for most talent limitations.

Successful people are not afraid to fail. They have the ability to accept their failures and continue on, knowing that failure is a natural consequence of trying. The law of failure is one of the most powerful of all the success laws because you only really fail when you quit trying.

Read the whole article here.

The Team Culture Aspect of Success

It is a widely held belief in the sports world that the team culture can have a big impact on how a team functions and performs. How team members, think, feel, behave, and perform are all influenced by the environment in which they practice and compete.

For example, have you ever been on a “downer” team? I’m talking about one that is permeated with negativity, unhealthy competition, and conflict? It sure doesn’t feel good and it can definitely interfere with your performing your best. As an athlete, it’s difficult to do much about it; all you can do is accept it or find another team. But, as a coach, you can have a big impact on how your team functions. Continue reading...

Do's and Don'ts for Sports Parents

Do for Yourself:

• Get vicarious pleasure from your children's participation, but do not become overly ego-involved.

• Try to enjoy yourself at competitions. Your unhappiness can cause your child to feel guilty.

• Look relaxed, calm, positive and energized when watching your child compete. Your attitude influences how your child feels and performs.

• Have a life of your own outside of your child's sports participation.

Do with Other Parents:

• Make friends with other parents at events. Socializing can make the event more fun for you.

• Volunteer as much as you can. Youth sports depend upon the time and energy of involved parents.

• Police your own ranks: Work with other parents to ensure that all parents behave appropriately at practices and competitions.

Do with Coaches:

• Leave the coaching to the coaches.

• Give them any support they need to help them do their jobs better.

• Communicate with them about your child. You can learn about your child from each other.

• Inform them of relevant issues at home that might affect your child at practice.

• Inquire about the progress of your children. You have a right to know.

• Make the coaches your allies.

Do for your Children:

• Provide guidance for your children, but do not force or pressure them.

• Assist them in setting realistic goals for participation.

• Emphasize fun, skill development and other benefits of sports participation, e.g., cooperation, competition, self-discipline, commitment.

• Show interest in their participation: help them get to practice, attend competitions, ask questions.

• Provide a healthy perspective to help children understand success and failure.

• Emphasize and reward effort rather than results.

• Intervene if your child's behavior is unacceptable during practice or competitions.

• Understand that your child may need a break from sports occasionally.

• Give your child some space when need. Part of sports participation involves them figuring things out for themselves.

• Keep a sense of humor. If you are having fun and laughing, so will your child

• Provide regular encouragement.

• Be a healthy role model for your child by being positive and relaxed at competitions and by having balance in your life.

• GIVE THEM UNCONDITIONAL LOVE: SHOW THEM YOU LOVE THEM WHETHER THEY

• WIN OR LOSE!!!

Don’t for Yourself:

• Base your self-esteem and ego on the success of your child's sports participation.

• Care too much about how your child performs.

• Lose perspective about the importance of your child's sports participation.

Don’t with Other Parents:

• Make enemies of other parents.

• Talk about others in the sports community. Talk to them. It is more constructive.

Don’t with Coaches:

• Interfere with their coaching during practice or competitions.

• Work at cross purposes with them. Make sure you agree philosophically and practically on why your child is playing sports and what he or she may get out of sports.

Don’t with Your Children

• Expect your children to get anything more from their sports than a good time, physical fitness, mastery and love of a lifetime sport and transferable life skills.

• Ignore your child's bad behavior in practice or competitions.

• Ask the child to talk with you immediately after a competition.

• Show negative emotions while watching them perform.

• Make your child feel guilty for the time, energy and money you are spending and the sacrifices you are making.

• Think of your child's sports participation as an investment for which you expect a return.

• Live out your own dreams through your child's sports participation.

• Compare your child's progress with that of other children.

• Badger, harass, use sarcasm, threaten or use fear to motivate your child. It only demeans them and causes them to dislike you.

• Expect anything from your child except their best effort.

• EVER DO ANYTHING THAT WILL CAUSE THEM TO THINK LESS OF THEMSELVES OR OF YOU!

You can help your child become a strong competitor by...

• Emphasizing and rewarding effort rather than outcome.

• Understanding that your child may need a break from sports occasionally.

• Encouraging and guiding your child, not forcing or pressuring them to compete.

• Emphasizing the importance of learning and transferring life skills such as hard work,

• Self-discipline, teamwork, and commitment.

• Emphasizing the importance of having fun, learning new skills, and developing skills.

• Showing interest in their participation in sports, asking questions.

• Giving your child some space when needed. Allow children to figure things out for themselves.

• Keeping a sense of humor. If you are having fun, so will your child.

• Giving unconditional love and support to your child, regardless of the outcome of the day's competition.

• Enjoying yourself at competitions. Make friends with other parents, socialize, and have fun.

• Looking relaxed, calm, and positive when watching your child compete.

• Realizing that your attitude and behaviors influences your child's performance.

• Having a balanced life of your own outside sports.

Don’t . .

• Think of your child's sport participation as an investment for which you want a return.

• Live out your dreams through your child.

• Do anything that will cause your child to be embarrassed.

• Feel that you need to motivate your child. This is the child's and coach's responsibility.

• Ignore your child's behavior when it is inappropriate, deal with it constructively so that it does not happen again.

• Compare your child's performance to that of other children.

• Show negative emotions while you are watching your child at a competition.

• Expect your child to talk with you when they are upset. Give them some time.

• Base your self-esteem on the success of your child's sport participation.

• Care too much about how your child performs.

• Make enemies with other children's parents or the coach.

• Interfere, in any way, with coaching during competition or practice.

• Try to coach your child. Leave this to the coach.

Stress Relievers for Parents with Children in Sports

• Laugh. Go to a funny movie or do something silly with a friend.

• Take a 10 minute break and walk around the block.

• Light a candle and take a bubble bath in the dark.

• Do nothing. . . and don't feel guilty about it!

• Pay off your credit cards.

• Turn off the T.V.

• Read a book or magazine.

• Read a classic book as a family.

• Make time for a hobby or activity you really love.

• Meet a good friend for coffee.

• Write your child's coach a note of thanks.

• Smile at someone.

• Sit outside on a warm summer night and watch the stars come out.

• Concede that you don't have to be proven right every time.

• As a family get involved with a project that helps someone less fortunate.

• Set up a carpool schedule for your kids activities so you don't spend your life in the car.

• Set aside a day with no outside activities scheduled.

• Go to the church or synagogue of your choice.

• Schedule a meeting with your child's coach to discuss her progress and establish agreed upon goals.

• Avoid initiating or participating in the gym gossip.

About the Author:

Michael A. Taylor an Instructor for the Stanford University based Positive Coaching Alliance, a long-time member of the United States Elite Coaches Association and a former gym owner.

Smothered in Praise

APPEARED IN PRINT: SUNDAY, OCT. 3, 2010, PAGE G1

She’s so advanced!” beams the proud parent. “He’s just so smart!” boasts the doting grandmother.

So goes another day in the Lake Wobegon land of a pediatric office, where all the children are above average.

Not to disparage anyone, for who would contest the prerogative of kin to exult their beloved child? Would that all children be so adored.

Yet what happens when a child, since before she could talk, constantly hears that she’s smart? Does self-awareness of one’s smartness translate into fearless confidence later on? Or does it instill fearful hesitance to try new things, fearing failure?

Kids today are being raised in an age where self-confidence is everything. A positive attitude, not perseverance, is the answer to the riddle of success. At home and school, children are saturated with messages that they’re doing great — that they are great, innately so. They have what it takes.

Having been lauded from cradle to college for their greatness, too many leave the nest — if they leave at all — without the faintest idea of what greatness is, or what it demands. Greatness is always there and always theirs, and failure is always someone else’s fault.

According to a survey conducted by Columbia University, 85 percent of parents believe in the importance of telling their kids early and often that they’re smart. The presumption is that if a child believes he’s smart — having been told so, repeatedly — he won’t be intimidated by new challenges.

Constant praise is an angel on the shoulder, daily whispering the words of Al Franken’s Stuart Smalley: “You’re good enough, you’re smart enough, and doggone it, people like you!”

But a growing body of research strongly suggests that it works the other way around. Giving kids the tag of “smart” does not insulate them from underperforming. It actually might undermine their prospects of success.

Researchers long have noticed that large numbers of the smartest children severely underestimate their own aptitude. They lack confidence in their ability to tackle novel tasks. Smart children, to whom many things come very quickly, often give up just as quickly when things don’t.

Children afflicted with this lack of perceived competence adopt lower standards for success and expect less of themselves. They too readily divide the world into things they are naturally good at and things they are not. They pay rapt attention to the devil on the other shoulder, who shouts, “You’re not good at this!” Unless otherwise nudged or shoved into a new activity, too often they heed an internal warning to refrain.

Always having been praised for their intelligence, smart children often overlook or discount the importance of effort. My smarts are the key to my success, the kid’s reasoning goes, therefore I don’t need to put out effort. Expending effort is public proof that you can’t cut it on the strength of your natural gifts.

Researchers have measured the effect of praising schoolchildren for their intelligence (“you’re so smart at this”), as compared to the effect of praising them for their effort (“you must have worked really hard at this”). What is consistently found is that children praised for their effort subsequently choose harder tasks, while those praised for their intelligence choose easier ones.

Over and again, the “smart” kids took the easy way out.

The adverse effect of praise for innate intelligence on performance holds true for students of every socioeconomic class. And it knocks down both boys and girls — the very brightest girls, especially, are found most likely to collapse after failure.

Children praised solely and repeatedly for their intelligence are in effect being told the name of the game is to look smart, to not risk making mistakes and being embarrassed. Failure is assumed as evidence that they aren’t really smart at all.

Kids must of course be allowed to fail, and to learn from their failures. Let us do away with the hodgepodge of ribbons, pins and mass-produced certificates that commemorate everything but real achievement. No more banning schoolyard games that inherently produce winners and losers. If we are constantly rewarding mediocrity, how will children learn the difference between the excellent and the ordinary?

Brushing aside failure and just focusing on the positive is not being a good parent, caregiver or teacher. A child who comes to believe failure is something so terrible that the adults in his life can’t acknowledge its existence is a child deprived of the opportunity to discuss mistakes — and a child who therefore can’t learn from them.

Our job instead is to instill in children a firm belief that the way to bounce back from failure is to work harder. In other words, try, try again.

People with persistence — the ability to repeatedly respond to failure by exerting more effort instead of simply giving up — rebound well and can sustain their motivation through long periods of delayed gratification. Children who receive rewards too frequently and superfluously will not develop persistence; instead, they’ll quit when the rewards disappear.

Praise is important, just not vacuous praise. Researchers have found that to be effective praise needs to be specific, credible and sincere. Again, intelligence alone should not be praised. Effort, true skill or talent, insight, intention, patience, humility, tolerance, and receptiveness to constructive criticism — combined with a determination to learn from it — should be praised.

Instead of saying “you’re so smart,” parents and teachers should say, “I like how you keep trying.” Emphasizing and praising effort gives a child a variable that they can control. They come to see themselves as masters of their destiny. Praising natural intelligence removes destiny from the child’s control and provides no good formula for responding to a failure.

Kids should be taught that intelligence is something developed rather than innate. Kids taught thusly are more likely to make effort, to strive no matter the challenge. The concept of teaching kids that the brain is a muscle, and that giving it a harder workout makes you smarter, has been shown to greatly improve young school-age children’s study habits and grades.

We should be honest with our children if we feel that they are capable of better work. As parents and as teachers, we should not be there to make children feel better, but to encourage them to do better.

As parents, what’s the bottom line? Love your kids unconditionally. But unconditional love does not require offering unconditional praise.

While there’s no mistaking the allure of a life outlook in which you’ll make every basket, get every job and reach every star, teaching your children such an outlook does not prepare them for adulthood. And preparing our children for adulthood is our first and largest responsibility as parents.

We should not implant the absurd notion of, “Of course you can do it.” Success is not bought and delivered with the currency of happy thoughts. Success is earned through tenacity, patience, scholarship, sacrifice, self-discipline and due diligence.

The best slogan to live by and to teach our children isn’t all that inspiring, but it’s the truth: Expect failure, but keep trying. Joy is found in the striving. And with persistence, you will have successes.

Savor them and treasure them, for you’ve earned them through hard work.